Scroll to:

Epizootic situation on contagious porcine diseases in the Republic of Burundi

https://doi.org/10.29326/2304-196X-2025-14-2-148-155

Abstract

Introduction. In Burundi, where 80% of the population are engaged in livestock farming, industries with short reproduction cycles (pig farming, poultry farming) prevail. Despite government support measures and annually increasing pig population, the country has been unable to fully meet the demand for livestock products. This is due to numerous problems in the sector, with infectious animal diseases being the primary issue. Infectious disease outbreaks can have catastrophic consequences for the human population, including threats to food security, loss of access to animal protein, increased production costs due to the need for expensive disease control measures, and risks to human health in case of zoonotic diseases.

Objective. The aim is to study the nosological profile of porcine infectious diseases, identify factors contributing to animal infections and assess the swine erysipelas epizootic situation in the Republic of Burundi from 2018 to 2023.

Materials and methods. Data of annual reports of the General Directorate of Animal Health and test results of the National Veterinary Laboratory of Burundi (2018–2023) were used to analyze the epizootic situation on infectious porcine diseases. Retrospective and epizootiological analyses were conducted and variational statistical methods were applied.

Results. The analysis revealed a high prevalence of porcine parasitic diseases, which is attributed to the equatorial climate. Within the overall structure of infectious diseases, parasitic infestations ranked first, growing from 81.2% in 2018 to 92.8% in 2023. Bacterial infections were the second most widespread, rising from 3.6% in 2018 to 6.3% in 2023. A steady increase in swine erysipelas cases was observed: in 2023 the number of cases was 1.7 times higher than in 2022 and seven times higher than in 2020. Moreover, the number of provinces where the disease is detected is annually growing. Swine erysipelas is currently reported in 12 out of 18 Burundian provinces.

Conclusion. The Republic of Burundi suffers significant annual losses due to animal deaths caused by infectious disease outbreaks. In the absence of specific disease prevention measures (particularly for erysipelas) and weak veterinary control of animal movements between households, infections spread rapidly. Therefore, studying the epizootic situation and developing measures to stabilize it under local conditions is a crucial scientific and practical task for ensuring biological and food security.

Keywords

For citations:

Koshchaev A.G., Niyongabo H., Gorkovenko N.E., Nimbona C., Ntirandekura J. Epizootic situation on contagious porcine diseases in the Republic of Burundi. Veterinary Science Today. 2025;14(2):148-155. https://doi.org/10.29326/2304-196X-2025-14-2-148-155

INTRODUCTION

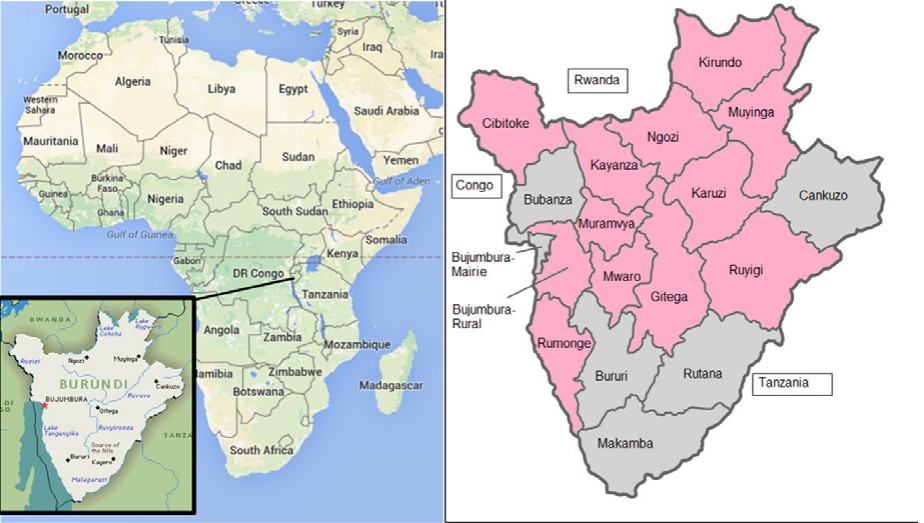

The Republic of Burundi is situated in East Africa between the Congo River basin and the eastern highlands. The country shares borders with Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the east, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, with its southwestern frontier extending along the shores of Lake Tanganyika. Burundi’s topography is characterized by a highland plateau featuring dramatic elevation variations ranging from 772 to 2,684 meters above sea level, the climate is equatorial.

Due to the relief features, Burundi has a wide variety of natural and climatic zones. The average annual temperature ranges from 17 to 23 °C. The country receives substantial precipitation, averaging 1,500 mm annually. Rainy seasons last from February to May and from September to December [1][2].

With a population of 13.2 million (2023), Burundi has one of Africa’s highest population densities at 442 people/km². The agricultural sector employs 80% of the workforce, with livestock production accounting for 14% of national gross domestic product (GDP) and 29% of agricultural GDP. However, the country faces growing pressure on land resources, particularly due to shrinking pasture areas. This has led to a shift toward livestock species with shorter reproduction cycles, and many farmers are showing interest in pig farming. Pig and poultry farming are gaining popularity as an alternative to cattle breeding, especially among low-income families. Over 79.2% of households own livestock, 12.9% of them have at least one pig [3].

Over the past few years, the Government of Burundi, in collaboration with international trade partners, has actively supported the pig breeding sector through several key initiatives. This bilateral cooperation has facilitated implementation of specialized breeding projects to develop improved pig breeds and establishment of modern animal breeding centers across the country.

Pursuant to Presidential Decree No. 100/087 of 26 July 2018 “On the Organizational Structure of the Ministry of Environment, Agriculture and Livestock, the Directorate General of Livestock” includes three divisions:

– Directorate of Animal Health, including the single service of the National Veterinary Laboratory (NVL);

– Directorate of Development of Livestock Farms, including the single service of the National Centre for Artificial Insemination (CNIA);

– Fisheries Development Authority, including the single service of the National Center for Research and Development of Fisheries and Aquaculture (CNDAPA).

The mission of the Directorate for Animal Health is to prevent spread of animal diseases in general and domestic animal diseases in particular [4].

Despite government support initiatives, the anticipated expansion of the national pig population has failed to achieve projected targets. This shortfall primarily stems from challenges confronting the sector, most notably – persistent outbreaks of infectious animal diseases, including zoonoses [5].

Swine erysipelas represents one of the most economically impactful diseases affecting pig production in Burundi. The infection primarily spreads among healthy pigs through consumption of contaminated feed and water [6][7]. It is caused by Erysipelothrix spp., that are rod-shaped gram-positive facultative anaerobic bacteria. Only eight species belong to this genus, among which is the most frequently isolated Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae [8-10]. While pigs serve as the main reservoir for this bacterium, E. rhusiopathiae has also been identified in various domestic animals, fish and birds [11][12]. In humans, the pathogen causes erysipeloid disease, predominantly affecting individuals in high-risk occupations including veterinarians, butchers, farmers, and fishermen [13-15]. Although human E. rhusiopathiae infections remain relatively uncommon, surveillance data indicate a rising trend in human cases in recent years [10][16]. Due to its zoonotic potential, swine erysipelas is currently recognized by the World Health Organization as a significant zoonotic disease [17].

The aim of the study was to investigate the nosological characteristics of swine infectious pathology, identify the factors contributing to animal infection, and assess the swine erysipelas epizootic situation in the Republic of Burundi for the period from 2018 to 2023.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was carried out at the Department of Microbiology, Epizootology and Virology at the Kuban State Agrarian University named after I. T. Trubilin as part of the research and development project: “Improving methods of diagnosis, treatment and prevention of diseases in food-producing animals, poultry and fur animals” (Registration No. 121032300041-1).

To analyze the epizootic situation with regard to porcine infectious diseases in the Republic, we used data from the annual reports of the Directorate General of Livestock, as well as the study results of the National Veterinary Laboratory of the Republic of Burundi for 2018–2023. In the course of the work we performed a retrospective and epizootiological analysis and applied methods of variational statistics.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

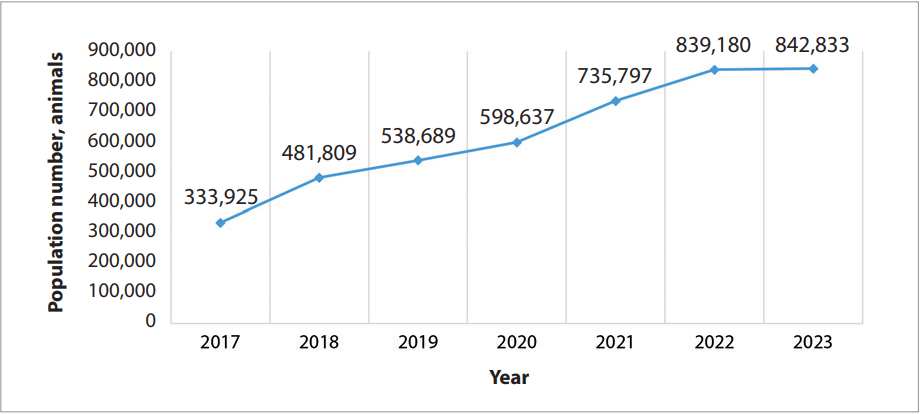

An analysis of statistical data on pig farming development in the Republic of Burundi revealed a consistent upward trend in livestock numbers during the study period (Fig. 1). This growth was facilitated through collaborative efforts between public and private organizations to establish supportive socio-economic conditions for pig-rearing households [18]. The country has implemented a “solidarity chain” system, where breeding centers distribute pigs free of charge to small farms and households, with recipients subsequently providing an equivalent number of offspring to animal-deprived households.

However, a significant number of pigs die due to inappropriate conditions, such as inadequate sanitation in pig houses, poor-quality feed and infectious diseases.

The indoor pig-rearing system predominates in Burundian households. Notably, over 70% of household pig facilities are constructed without adhering to World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) recommendations [19], a key factor facilitating the emergence and spread of infectious and parasitic diseases. Most traditional pig houses feature wooden structures with clay-filled cracks, lack proper roofing or have fragile roof coverings, and typically receive no regular cleaning. In contrast, a minority of modernized facilities include designated feeding areas, replaceable bedding, proper liquid manure drainage, concrete floors, brick walls and durable roofing materials.

Figure 2 shows the quantitative data for traditional and modernized pig-rearing facilities.

While the total number of pig housing facilities has increased, the proportion of those meeting modern standards has declined steadily from 29.85% in 2018 to 25.35% in 2023, reaching the minimum in 2019 (20.54%). Consequently, over 70% of pig production facilities in the country fail to meet basic zoohygienic requirements, which may significantly increase the risk of infectious and parasitic disease outbreaks. Another contributing factor to contagious disease transmission is the inadequate monitoring system for disposal of animal carcasses and slaughterhouse waste, as many pig owners dispose of biological waste in open landfills accessible to scavengers.

Burundi’s geographical location and tropical climate create favorable conditions for numerous infectious animal diseases (Table 1), including several zoonoses with epizootic and epidemic manifestations that occasionally occur.

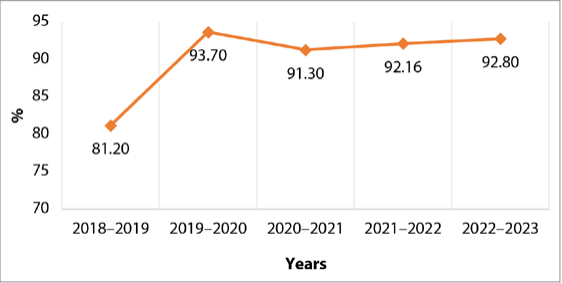

The animal disease situation in the country is impacted by the equatorial climate, which accounts for the overwhelming predominance of parasitic infections among swine contagious diseases [20, 21]. Between 2018 and 2023, the reported cases of swine invasive diseases remained consistently high, representing approximately 92% of all swine infectious pathologies (Fig. 3).

It is important to note that veterinary services in Burundi do not routinely conduct epizootiological monitoring to detect swine infectious disease pathogens or confirm their absence. Diagnostic testing to determine the cause of animal deaths is performed only in cases of mass mortality. Currently, infectious disease diagnosis in Burundi relies on microbiological (microscopy, culturing), serological (ELISA, agglutination, microagglutination tests), and molecular genetic (PCR) methods, but only when clinical symptoms or mass mortality events occur. In case of suspected parasitic diseases, clinical and microscopic examinations are primarily used, with post-mortem diagnostics occasionally performed during necropsies of deceased or emergency-slaughtered animals. Table 2 presents registered and laboratory-confirmed cases of swine infectious diseases in Burundi over five years, based on annual reports from the General Directorate of Animal Health.

The analysis of swine infectious disease prevalence in Burundi revealed that African swine fever (ASF) accounted for the highest case numbers until 2021. However, reported ASF cases declined by over 3.5-fold beginning in 2020, with no cases recorded in 2023. The ASF-freedom has been achieved through import and export restrictions on pigs. The movement of pigs within the borders of Burundi has been limited due to the unfavorable epizootic situation in neighboring countries [22][23]. Currently, all international swine imports are exclusively processed through the Burundi Institute of Agricultural Sciences (ISABU), with mandatory diagnostic testing and quarantine measures.

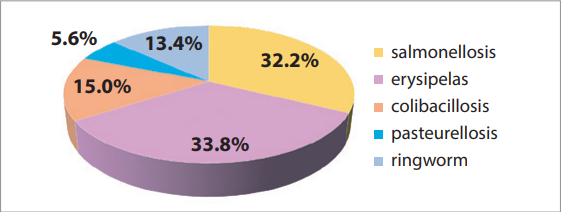

It should be emphasized that among viral swine diseases only ASF has been reported in the Republic, which is likely to reflect limited laboratory capacity for viral diagnosis. While classical swine fever outbreaks were recorded before 2018, no cases have been detected in recent years. Since 2023, bacterial infections have become predominant in swine pathology (Fig. 4), with erysipelas (33.8%) and salmonellosis (32.2%) representing the most prevalent diseases. Other frequently diagnosed conditions include colibacillosis (15.0%) and ringworm (13.4%) in domestic pig populations.

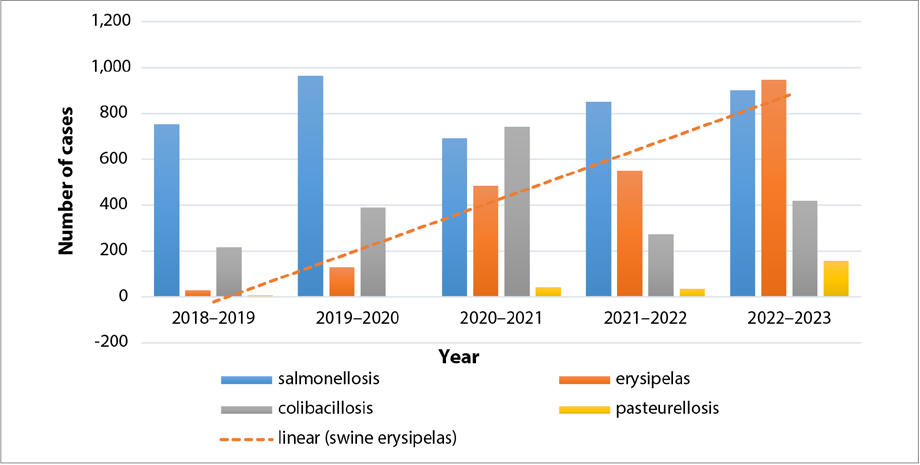

A graphical representation of five-year trend of swine bacterial disease number in the Republic of Burundi clearly shows cyclical fluctuations in salmonellosis and colibacillosis prevalence in pigs. At the same time, the swine erysipelas occurrence level is steadily increasing. Notably, erysipelas cases increased 1.7-fold in 2023 as compared to 2022, and surged more than 7-fold relative to 2020 levels (Fig. 5). Of particular concern is the absence of erysipelas vaccination programs in Burundi. Diagnostic capabilities have improved significantly since 2019, transitioning from purely clinical diagnosis to laboratory confirmation using bacteriological culturing and enzyme immunoassay methods.

A study of the territorial distribution of swine erysipelas in the Republic showed that the number of provinces where the disease is registered is growing every year (Table 3).

Between 2018 and 2020 swine erysipelas was confined to a single province. However, the disease expanded to 5 provinces by 2022 and reached 9 provinces by 2023. Cumulatively, outbreaks were documented in 12 of Burundi’s 18 provinces over this five-year period (Fig. 6).

The provinces where swine erysipelas has not been detected are located in southern regions (Bururi, Rutana, Makamba), the extreme eastern province (Cankuzo), and northwestern areas (Bubanza and Bujumbura Mairie). Swine erysipelas outbreaks have been confirmed in all central provinces of Burundi. Despite movement restrictions between provinces and districts, reported erysipelas cases continue to rise steadily, that may be attributed to growth in pig populations, inadequate livestock farming practices, illegal movement of animals and/or animal products across or within the borders and improved diagnostic efforts by the National Veterinary Laboratory.

The escalating incidence of swine erysipelas raises significant concerns among competent authorities and veterinary specialists in Burundi. The pathogen demonstrates prolonged environmental persistence in soil and other reservoirs due to the country’s humid equatorial climate, facilitating the establishment of endemic disease outbreaks. Moreover, many farmers tend to conceal outbreaks and animal deaths, and improperly dispose of carcasses in open landfills accessible to scavengers, exacerbating transmission risks. In the absence of erysipelas vaccination programs, the current epizootic situation poses a serious threat.

Fig. 1. Dynamics of pig population in the Republic of Burundi in 2017–2023

Fig. 2. Proportion of traditional to modernized pig housing in Burundi households from 2018 to 2023

Table 1

Prevalence of contagious porcine diseases in the Republic of Burundi from 2018 to 2023 (according to the General Directorate of Animal Health)

|

Disease group by agent type |

Reported cases by year, % |

||||

|

2018–2019 |

2019–2020 |

2020–2021 |

2021–2022 |

2022–2023 |

|

|

Bacterial |

3.60 |

3.20 |

5.20 |

4.80 |

6.30 |

|

Parasitic |

81.20 |

93.70 |

91.30 |

92.16 |

92.80 |

|

Viral |

14.50 |

2.50 |

2.70 |

1.70 |

0 |

|

Fungal |

0.63 |

0.54 |

0.76 |

1.40 |

0.97 |

Fig. 3. Dynamics of reported cases of porcine parasitic diseases in the Republic of Burundi from 2018 to 2023

Fig. 4. Reported cases of porcine bacterial infectious diseases in the Republic of Burundi in 2023

Table 2

Nosological profile of infectious porcine diseases in the Republic of Burundi from 2018 to 2023 (according to the General Directorate of Animal Health)

|

Nosological unit |

Number of registered cases by year |

|||||||||

|

2018–2019 |

2019–2020 |

2020–2021 |

2021–2022 |

2022–2023 |

||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

African swine fever |

4,093 |

77.5 |

1,164 |

40.0 |

1,034 |

31.4 |

598 |

21.3 |

– |

– |

|

Salmonellosis |

753 |

14.3 |

965 |

33.2 |

694 |

21.1 |

853 |

30.4 |

902 |

32.2 |

|

Erysipelas |

31 |

0.6 |

130 |

4.5 |

486 |

14.8 |

552 |

19.6 |

948 |

33.8 |

|

Colibacillosis |

218 |

4.1 |

392 |

13.5 |

743 |

22.6 |

274 |

9.8 |

422 |

15.0 |

|

Pasteurellosis |

8 |

0.15 |

4 |

0.14 |

45 |

1.4 |

38 |

1.4 |

158 |

5.6 |

|

Ringworm |

178 |

3.4 |

253 |

8.7 |

290 |

8.8 |

495 |

17.6 |

375 |

13.4 |

|

n – number of cases. |

||||||||||

Fig. 5. Dynamics of reported cases of porcine bacterial infectious diseases in the Republic of Burundi from 2018 to 2023

Fig. 6. Administrative divisions of the Republic of Burundi (provinces with reported cases of swine erysipelas are shown in pink)

Table 3

Distribution of swine erysipelas in the provinces of the Republic of Burundi from 2018 to 2023 (according to the National Veterinary Laboratory)

|

Provinces |

Period (years) |

||||

|

2018–2019 |

2019–2020 |

2020–2021 |

2021–2022 |

2022–2023 |

|

|

Bujumbura Rural |

– |

– |

– |

– |

62 |

|

Gitega |

– |

– |

11 |

35 |

198 |

|

Karuzi |

– |

130 |

– |

– |

– |

|

Kayanza |

– |

– |

– |

– |

76 |

|

Kirundo |

– |

– |

– |

– |

204 |

|

Mwaro |

– |

– |

– |

– |

4 |

|

Muyinga |

– |

– |

– |

– |

48 |

|

Muramvya |

– |

– |

– |

7 |

– |

|

Ngozi |

– |

– |

– |

– |

143 |

|

Ruyigi |

– |

– |

160 |

160 |

– |

|

Rumonge |

– |

– |

315 |

124 |

145 |

|

Cibitoke |

31 |

– |

– |

226 |

68 |

|

Total for the country |

31 |

130 |

486 |

552 |

948 |

CONCLUSION

For the Republic of Burundi, pig farming (whether on private, small-scale, or semi-commercial farms) is a crucial component of food security, ensuring the population’s access to animal protein. The government has taken substantial efforts to supply farms with livestock and promote pig farming as a key industry with a short production cycle. However, the communities suffer significant annual losses due to infectious disease outbreaks. These losses stem from multiple factors, including unfavorable climatic conditions, on the one hand, and low livestock farming standards, on the other. A major contributing factor is inadequate epizootic control by the state veterinary service, as well as lack of vaccination programs, particularly those against swine erysipelas. The incidence of swine erysipelas has risen sharply in recent years. In 2023, reported cases increased by over 1.7 times compared to 2022 and more than seven-fold compared to 2020. This trend has led to the establishment and maintenance of persistent, endemic outbreaks across the country. Between 2018 and 2023, the disease was recorded in 12 of Burundi’s 18 provinces. Given these findings, Burundi’s veterinary authorities must prioritize systematic action in three key areas: 1) epizootiological monitoring of swine infectious diseases, which will enable early outbreak detection, control and containment of infectious diseases, particularly swine erysipelas, in the country; 2) training livestock owners in essential biosecurity practices, following WOAH guidelines (separation, cleaning and disinfection); 3) development of a national policy for modernization of pig farming through strategic policies, including measures to ensure affordable feed supplies.

References

1. La Géographie du Burundi. Ministère des Affaires Etrangères du Burundi. https://www.mae.gov.bi (in French)

2. Enquête Nationale Agricole du Burundi, 2016–2017. Résultats de la Campagne Agricole. Juin 2018. https://bi.chm-cbd.net/sites/bi/files/2019-10/enab_2016_2017.pdf (in French)

3. Le Burundi en Bref. Ministère des Affaires Etrangères et de la Coopération au Développement au Burundi. Juin 24, 2018. https://www.mae.gov.bi (in French)

4. Décret No. 100/087 du 26 juillet 2018 portant Organisation du Ministère de l’Environnement, de l’Agriculture et de l’Elevage. https://presidence.gov.bi/2018/07/31/decret-n100087-du-26-juillet-2018-portant-organisation-du-ministere-de-lenvironnement-de-lagriculture-et-de-lelevage (in French)

5. Mbazumutima A. Vers le boom de la filière porcine? IWACU. 14.01.2024. https://www.iwacu-burundi.org/vers-le-boom-de-la-filiere-porcine (in French)

6. Gosmanov R. G., Ravilov R. Kh., Galiullin A. K., Volkov A. Kh., Nurgaliyev F. M., Yusupova G. R., Andreeva A. V. Private veterinary and sanitary microbiology and virology: study-book. Saint Petersburg; 2022. 316 p. (in Russ.)

7. Ramirez A. Laboratory diagnostics: Erysipelas. pig333.com: Professional Pig Community. 16 August 2021. https://www.pig333.com/articles/laboratory-diagnostics-for-erysipelas-in-pigs_17507

8. Vaissaire J. Le rouget du porc: diagnostic, traitement et prévention. Le Point Vétérinaire. No. 254 du 01.04.2005. https://www.lepointveterinaire.fr/publications/le-point-veterinaire/article/n-254/le-rouget-du-porc-diagnostic-traitement-et-prevention.html (in French)

9. Le rouget chez l’animal et l’homme. Office fédéral de la sécurité alimentaire et des affaires vétérinaires. https://www.blv.admin.ch/blv/fr/home/tiere/tierseuchen/uebersicht-seuchen/alle-tierseuchen/Rotlauf.html (in French)

10. Gerber P. F., MacLeod A., Opriessnig T. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae serotype 15 associated with recurring pig erysipelas outbreaks. Veterinary Record. 2018; 182: 635. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.104421

11. Opriessnig T., Coutinho T. A. Erysipelas. In: Diseases of Swine. Eds. J. J. Zimmerman, L. A. Karriker, A. Ramirez, K. J. Schwartz, G. W. Stevenson, J. Zhang. 11th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2019; 835–843. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119350927.ch53

12. Opriessnig T., Forde T., Shimoji Y. Erysipelothrix spp.: Past, present, and future directions in vaccine research. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2020; 7:174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00174

13. Veraldi S., Girgenti V., Dassoni F., Gianotti R. Erysipeloid: a review. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2009; 34 (8): 859–862. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03444.x

14. Kiratikanon S., Thongwitokomarn H., Chaiwarith R., Salee P., Mahanupab P., Jamjanya S., et al. Sweet syndrome as a cutaneous manifestation in a patient with Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae bacteremia: a case report. IDCases. 2021; 24:e01148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01148

15. Challa H. R., Tayade A. C., Venkatesh S., Nambi P. S. Erysipelothrix bacteremia; is endocarditis a rule? Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 2023; 15 (1): 31–34. https://doi.org/10.4103/jgid.jgid_30_22

16. Rostamian M., Rahmati D., Akya A. Clinical manifestations, associated diseases, diagnosis, and treatment of human infections caused by Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: a systematic review. Germs. 2022; 12 (1): 16–31. https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2022.1303

17. Canotilho J., Abrantes A. C., Risco D., Fernández-Llario P., Aranha J., Vieira-Pinto M. First serologic survey of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae in wild boars hunted for private consumption in Portugal. Animals. 2023; 13 (18):2936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13182936

18. Plan National de Developpement du Burundi (PND Burundi 2018– 2027). https://presidence.gov.bi/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/PND-Burundi-2018-2027-Version-Finale.pdf (in French)

19. Good emergency management practice: the essentials. Ed. by N. Honhold, I. Douglas, W. Geering, A. Shimshoni, J. Lubroth. Rome: FAO; 2011. 126 p. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/ba0137e

20. Minani S., Spiessens E., Labarrière A., Niyokwizera P., Gasogo A., Ntirandekura J. B. et al. Occurrence of Taenia species and Toxoplasma gondii in pigs slaughtered in Bujumbura city, Kayanza and Ngozi provinces, Burundi. BMC Veterinary Research. 2024; 20 (1):589. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917024-04445-6

21. Minani S., Devleesschauwer B., Gasogo A., Ntirandekura J. B., Gabriël S., Dorny P., Trevisan C. Assessing the burden of Taenia solium cystic-ercosis in Burundi, 2020. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2022; 22 (1):851. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07849-7

22. Fasina F. O., Mtui-Malamsha N., Nonga H. E., Ranga S., Sambu R. M., Majaliwa J., et al. Semiquantitative risk evaluation reveals drivers of African swine fever virus transmission in smallholder pig farms and gaps in biosecurity, Tanzania. Veterinary Medicine International. 2024; 2024:4929141. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/4929141

23. Hakizimana J. N., Yona C., Kamana O., Nauwynck H., Misinzo G. African swine fever virus circulation between Tanzania and neighboring countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Viruses. 2021; 13 (2):306. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13020306

About the Authors

A. G. KoshchaevRussian Federation

Andrey G. Koshchaev, Academician of the RAS, Professor, Dr. Sci. (Biology), Professor of the Department of Biotechnology, Biochemistry and Biophysics,

13, Kalinina str., Krasnodar 350044.

H. Niyongabo

Russian Federation

Herménégilde Niyongabo, Postgraduate Student,

13, Kalinina str., Krasnodar 350044.

N. E. Gorkovenko

Russian Federation

Natalya E. Gorkovenko, Dr. Sci. (Biology), Associate Professor, Professor of the Department of Microbiology, Epizootology and Virology,

13, Kalinina str., Krasnodar 350044.

C. Nimbona

Burundi

Constantin Nimbona, PhD, Faculty of Agronomy and Bio-Engineering, Department of Animal Health and Productions,

2, Avenue de l’UNESCO, Bujumbura B. P. 1550.

J.-B. Ntirandekura

Burundi

Jean-Bosco Ntirandekura, PhD, Faculty of Agronomy and Bio-Engineering, Department of Animal Health and Productions,

2, Avenue de l’UNESCO, Bujumbura B. P. 1550.

Review

For citations:

Koshchaev A.G., Niyongabo H., Gorkovenko N.E., Nimbona C., Ntirandekura J. Epizootic situation on contagious porcine diseases in the Republic of Burundi. Veterinary Science Today. 2025;14(2):148-155. https://doi.org/10.29326/2304-196X-2025-14-2-148-155