Scroll to:

Creating a laboratory model of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae associated infection

https://doi.org/10.29326/2304-196X-2025-14-1-55-61

Abstract

Introduction. Respiratory mycoplasmosis and infectious synovitis are economically significant and notifiable avian diseases, therefore, the issue of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae control on poultry farms is of great importance. Vaccination is one of the ways to ensure specific prevention, however, when a vaccine is developed, its protective properties are assessed with special focus. Challenge does not always lead to the disease manifestation due to its predominantly chronic and factor-dependant nature.

Objective. Laboratory simulation of the factors that contribute to the disease manifestation and a histological analysis of pathological changes in the infected and vaccinated poultry.

Materials and methods. Seronegative and vaccinated 67-day-old Haysex white cross chickens were selected for the experimental purposes. We used S6 strain of Mycoplasma gallisepticum, WVU 1853 strain of Mycoplasma synoviae and A/chicken/Amursky/03/12/H9N2 strain of low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus.

Results.The associated infection of mycoplasmoses and low-pathogenicity avian influenza is manifested as a disease with pathohistological changes that include mild respiratory and joint disorders. Histological tests of the infected non-vaccinated poultry revealed damaged tracheal ciliated epithelium with desquamation. The poultry vaccinated against mycoplasmosis and experimentally infected showed no signs of epithelial separation, however, local submucosal edema was observed in the trachea. Non-vaccinated poultry infected with low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus H9N2, Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae demonstrated dystrophic changes and lymphocyte infiltration in the third eyelid gland which suggested an inflammation. Lymphocytic lung tissue infiltration was detected both in the vaccinated and non-vaccinated experimentally infected poultry. All groups of chickens, except for the control one, demonstrated lymphocyte depopulation in the cortical substance of the fabricium sac.

Conclusion. The study resulted in developing a challenge procedure for poultry using Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae agents, in defining conditions for clinical manifestation of mycoplasmoses, in detecting infection-caused pathological changes at the cellular level.

For citations:

Kozlov D.A., Volkov M.S., Chupina O.A., Moroz N.V., Irza V.N., Pronin V.V. Creating a laboratory model of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae associated infection. Veterinary Science Today. 2025;14(1):55-61. https://doi.org/10.29326/2304-196X-2025-14-1-55-61

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory mycoplasmosis and infectious synovitis are economically important diseases caused by Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae [1]. The peculiarity of these mycoplasmoses is their chronic nature with exacerbation resulting from reduced natural resistance or caused by stress factors of various origin [2]. Vaccination is one of the ways to prevent these diseases [3]. When vaccines are developed, special attention is paid to their protective properties demonstrated in the challenge tests. Taking into account that avian mycoplasmoses are factor-dependent, it is rather difficult to reproduce the infectious process in the laboratory. Thus, the issue of testing protective properties of vaccines against respiratory mycoplasmosis and infectious synovitis has become especially important in the antimicrobial resistance control time.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum causes respiratory mycoplasmosis in chickens and turkeys, with the following signs: rales, coughing, rhinorrhea, aerosacculitis. This disease is predominantly chronic, spreads slowly in the flock, mycoplasma-carriers frequently occur. The disease can be aggravated by such stress factors as vaccination, poor feeding, draughts, high concentration of ammonia in the air, etc. Post-mortem lesions resulting from respiratory mycoplasmosis include serous, serous-fibrinous or fibrinous exudate in the nasal cavity and suborbital sinuses. Tracheal mucosa is hyperemic, lungs are full of blood, pneumonia may occur. Pathognomonic sign consists in serous, serous-fibrinous or fibrinous aerosacculitis of thoracic or abdominal air sacs: with thickened and opaque walls and exudate accumulated in the cavity. The non-complicated form is characterized by no lesions of parenchymatous organs [4][5].

Mycoplasma synoviae is the pathological agent causing infectious avian synovitis, characterized by arthritis, tendovaginitis, synovitis and anemia. The disease clinical signs may include lameness, pale comb, stunting and swelling in the metatarsal and tibiotarsal joints, plantar surface of the paw, and thoracic bursa [6]. During subacute and chronic disease, the surface of the affected joints is macerated, covered with exudate crusts and necrotic masses [7][8][9]. Periarticular tissues and tendon sheaths in the affected joints are edematous, transparent exudate accumulates in the joint cavity; the chronic course is characterized by a significant amount of fibrinous masses [10]. The disease may also manifest itself as a respiratory syndrome indistinguishable from respiratory mycoplasmosis. Egg Apical Abnormalities (EAA) is believed to be a pathognomonic sign of infectious synovitis, which causes significant economic losses due to the need to cull table and hatching eggs [4][11].

Despite the extensive list of avian mycoplasmosis characteristics, such characteristics as chronic nature and factor-dependence create certain difficulties in creating infections in the laboratory.

It is difficult to assess protective properties of the vaccine developed for specific prophylaxis of chronic diseases. For acute infections, such as high-pathogenicity avian influenza and Newcastle disease, it is easy to assess vaccine protective properties in challenge tests; however, this method has significant limitations for chronic infections, including mycoplasmosis, because it is not always possible to reproduce well-pronounced clinical signs in the laboratory [12][13][14]. In addition, mycoplasmosis pathogens can persist in the body for a long time and remain undetected by the immune system (biological mimicry) [4][9][15].

Thus, creating a laboratory model of mycoplasmosis to assess protective properties of newly developed vaccines is assumed a timely and relevant task. Given that infections of mycoplasma origin belong to factor-dependent diseases, it was necessary to select a trigger for clinical manifestation [16][17]. For this purpose, a reproduction model of co-infection caused by M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae and low pathogenicity avian influenza virus (subtype H9N2) with zero intravenous pathogenicity index (IVPI = 0) was tested in the experiment. According to some foreign authors, co-infection with low pathogenicity avian influenza virus (H3N8) significantly affects M. gallisepticum pathogenesis [18]. Infection of clinically healthy birds with this pathogen in the laboratory does not lead to clinical signs. However, on poultry farms, the co-infection of low pathogenicity avian influenza and mycoplasmosis causes respiratory infection [10][19].

A laboratory-created model of mycoplasma and low pathogenicity avian influenza co-infection may be used both for assessing vaccine protective properties and for analyzing the role of each pathogen in the pathogenesis of mixt-infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains. Strains S6 of M. gallisepticum and WVU 1853 of M. synoviae were used during the experiment. Strain of low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus A/chicken/Amursky/03/12/H9N2 (hereinafter – H9N2) was used as a co-infecting agent (trigger).

Inactivated emulsion combined vaccine against respiratory mycoplasmosis and infectious synovitis, produced by the Federal Centre for Animal Health (pilot batch).

Infectious doses. M. gallisepticum culture with activity of 6.0 log2 hemagglutinating units and M. synoviae with activity of 3.0 log2 agglutinating units were used for infection. The infectious doses of low pathogenicity avian influenza virus was 10⁶ lg EID/0.5 cm³.

Poultry. Seronegative and vaccinated 67 day-old Hisex white egg cross chickens were used for the experimental purposes. The chickens were kept in the animal facilities of the Federal Centre for Animal Health, the keeping and feeding conditions corresponded to zoo-hygiene requirements.

The dose and method of infection. The infection pattern and methods are given in Table 1.

Table 1

Infection procedure (scheme and methods)

|

Group number |

Number of birds in the group |

Vaccine |

Infection |

|

1 |

10 |

Inactivated emulsion combined vaccine against respiratory mycoplasmosis and infectious synovitis (pilot batch) |

H9N2 (intranasally, ocularly); M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae (intranasally, ocularly, intramuscularly) |

|

2 |

10 |

Not vaccinated |

H9N2 (intranasally, ocularly); M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae (intranasally, ocularly, intramuscularly) |

|

3 |

10 |

Not vaccinated |

H9N2 (intranasally, ocularly) |

|

4 |

10 |

Not vaccinated |

M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae (intranasally, ocularly, intramuscularly) |

|

5 (control) |

5 |

Not vaccinated |

Was not carried out |

Clinical observation and post-mortem examination. During the whole experiment (35 days post vaccination), the experimental chickens were monitored to assess their general condition (mobility, body condition score, reaction to external stimuli, crowding, depression, feed and water refusal, etc.).

On day 14 post infection, the chickens were euthanized and post-mortem examination was performed to describe lesions in organs and tissues. Pieces of organs and tissues were sampled for histological tests.

All the experiments were carried out in accordance with Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on protection of animals used for scientific purpose.

Histological tests were conducted in the Center for preclinical tests located in the Federal Centre for Animal Health. Organ sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, examined microscopically and followed by taking photographs.

Serological tests. Levels of specific antibodies to M. gallisepticum and M. synoviae were measured in avian sera using ELISA test kits manufactured by the Federal Centre for Animal Health; antibodies to the avian influenza virus H9N2 subtype were detected using hemagglutination inhibition (HI) test kits also manufactured by the Federal Centre for Animal Health.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

On day 3 after infection of non-vaccinated chickens with a combination of H9N2 + M. gallisepticum + M. synoviae pathogens (group No. 2), mild respiratory symptoms were observed, in particular, the chickens were passive, had watery eyes, conjunctival injection (reported in 6 out of 10 chickens). Between days 5–10, the following signs were noted: persistent skin hyperemia spotted in featherless patches on the heads, watery eyes and rhinorrhea. Nasal exudate dried into scabs, which easily fall off by themselves (in 9 out of 10 chickens). At the same time, 5 chickens from the group showed a change in behavior consisting in hypodynamia. Post-mortem examination of chickens in this group revealed signs of catarrhal laryngotracheitis with petechial hemorrhages (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Petechial and striped hemorrhages on the tracheal mucosa in the non-vaccinated poultry after infection with H9N2 + M. gallisepticum + M. synoviae (photo by D. A. Kozlov)

On day 7 post infection, some chickens from group No. 2 demonstrated lameness, in addition the birds were apathetic. Pronounced swelling, skin cracks and exudation were observed on the plantar surface of the paws (Fig. 2). Chickens spend a very high proportion of their daylight hours in recumbency. Opening of the affected sole parts showed severe swelling of the soft tissues with serous exudate; the soft tissue was swollen and had a gel-like consistency. These signs may suggest an articular inflammation caused by infectious synovitis.

Fig. 2. Inflammation of the plantar surface of the foot in the non-vaccinated chicken on day 7 after infection with H9N2 + M. gallisepticum + M. synoviae: edema, exudation (photo by D. A. Kozlov)

In groups No. 1 (vaccinated against mycoplasmosis), No. 3 (infected with H9N2), No. 4 (infected with M. gallisepticum and M. synoviae) and No. 5 (negative control), no visible clinical abnormalities were observed.

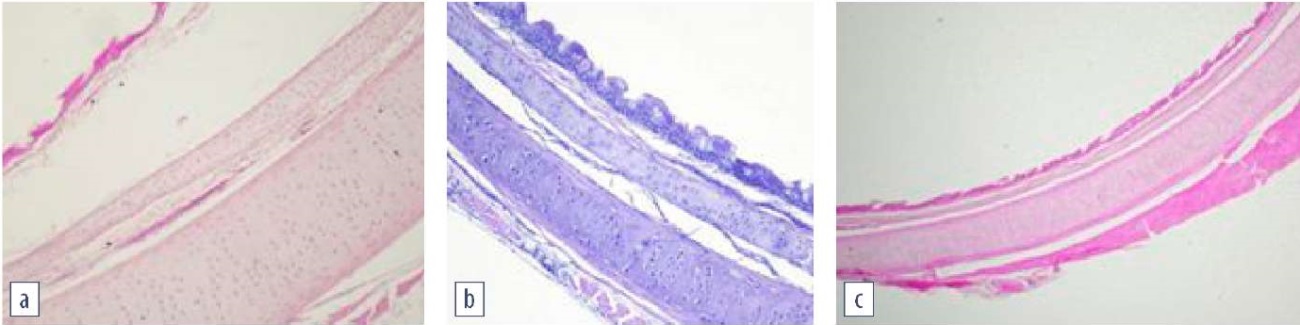

Morphological examination of the respiratory tract revealed that non-vaccinated poultry infected with H9N2 influenza virus, M. gallisepticum and M. synoviae (group No. 2) had disrupted ciliated epithelium in trachea with desquamation. Chickens vaccinated against mycoplasmosis infected with H9N2 + M. gallisepticum + M. synoviae (group No. 1), showed no signs of desquamation, however, local swelling of the submucosal layer was detected. Morphological structure of the trachea in control chickens was preserved, all layers were clearly visible (Fig. 3). At the same time, lymphocytic infiltration of lung tissue was detected in both groups of vaccinated and non-vaccinated chickens. All chicken groups, except for the control one, demonstrated a drop in lymphocytes in the cortical layer in the bursa of Fabricius, which proves activation of the immune system and the redistribution of lymphocytes after infection.

Fig. 3. Morphological structure of the trachea:

a – vaccinated and infected chicken; desquamation of the ciliated epithelium and submucosal swelling;

b – vaccinated and infected chicken; preserved tracheal structure;

c – control group; normal tracheal structure

(hematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification 100×;

photo by O. A. Chupina, V. V. Pronin)

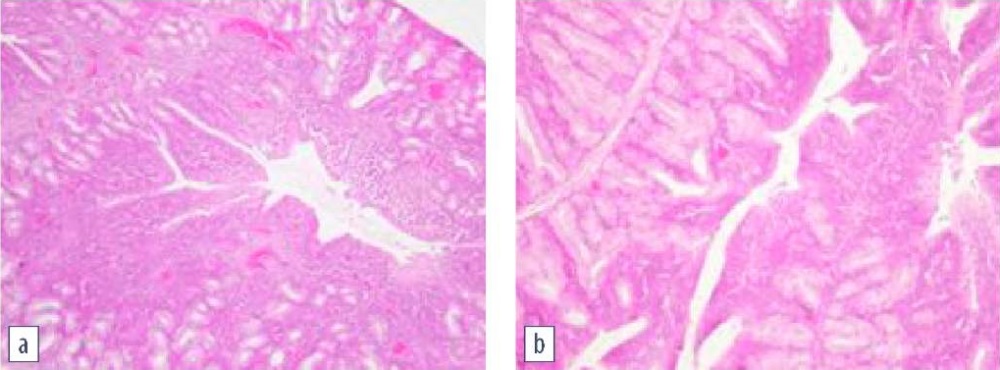

After infecting the non-vaccinated chickens using intranasal and ocular methods (H9N2 + M. gallisepticum + M. synoviae), the third eyelid gland demonstrated dystrophic changes and lymphocytic infiltration (Fig. 4), which suggested inflammation [16][20]. The group of the challenged vaccinated chickens, on the contrary, demonstrated a drop in lymphocyte in the third eyelid gland tissue.

Fig. 4. Histological examination of the third eyelid gland:

a – non-vaccinated infected chicken;

lymphocytic infiltration and dystrophic changes;

b – control group; normal structure of the third eyelid gland

(hematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification 100×;

photo by O. A. Chupina, V. V. Pronin)

All the experimental chickens, except for the control ones, showed signs of accidental thymus involution. White pulp of the spleen predominated over the red one in the non-vaccinated infected chickens. The experimental non-vaccinated chickens infected with H9N2 virus (group No. 3) had lymphocytic infiltration of kidneys and focal hemorrhages.

Histological tests of the intestines in all groups revealed that the duodenum serous and muscular membranes were preserved, autolysis was observed in the apical region of the intestinal villi and intestinal crypts were well expressed. Chyme was detected in the intestinal lumen. Cecal lymphoid follicles were identified on the border between the small and large intestine. They were structured, oval-shaped, without a pronounced reactive center.

The observed hyperemia of the vessels in various organs probably results from insufficient exsanguination.

The disease specificity after infection was confirmed by testing samples of chicken sera in ELISA and HI test. Table 2 shows mean antibody titers in vaccinated and non-vaccinated chickens before and after the challenge.

Table 2

Antibody titre before and after vaccination and infection

|

Group |

Mean antibody titer in group |

|||

|

Before challenge / vaccinations |

Post vaccination (day 21) |

Post Challenge |

||

|

day 7 |

day 14 |

|||

|

1 |

Mg = 102 ± 64 Ms = 34 ± 12 Н9N2 = 0 |

Mg = 2,688 ± 902 Ms = 2,830 ± 803 Н9N2 = 0 |

Mg = 4,013 ± 1,012 Ms = 3,590 ± 899 Н9N2 = 3.4 ± 0.33 |

Mg = 7,105 ± 1,812 Ms = 7,200 ± 1,679 Н9N2 = 4.3 ± 0.15 |

|

2 |

Mg = 84 ± 53 Ms = 12 ± 8 Н9N2 = 0 |

Not vaccinated |

Mg = 1,002 ± 402 Ms = 948 ± 899 Н9N2 = 3.3 ± 0.4 |

Mg = 3,013 ± 914 Ms = 2,590 ± 688 Н9N2 = 4.4 ± 0.3 |

|

3 |

Н9N2 = 0 |

Not vaccinated |

Н9N2 = 4.0 ± 0.44 |

Н9N2 = 4.5 ± 0.3 |

|

4 |

Mg = 66 ± 43 Ms = 24 ± 12 |

Not vaccinated |

Mg = 1,383 ± 212 Ms = 907 ± 64 |

Mg = 2,080 ± 765 Ms = 1,648 ± 966 |

|

5 |

Mg = 16 ± 9 Ms = 28 ± 12 Н9N2 = 0 |

Not vaccinated |

Not challenged |

|

|

Mg = 206 ± 82 Ms = 118 ± 89 Н9N2 = 0.6 ± 0.3 |

Mg = 304 ± 102 Ms = 194 ± 90 Н9N2 = 0.5 ± 0.2 |

|||

|

Mg – Mycoplasma gallisepticum; Ms – Mycoplasma synoviae. For Mg and Ms geometric mean ELISA titers were calculated in the group, for H9N2 the titers were expressed as HI log2. |

||||

The data obtained demonstrate that the immune system of the non-vaccinated chickens reacted to infection with each pathogen. At the same time, mycoplasmosis antibody titer in groups No. 2 and 4 significantly increased after infection (age-related), indicating mycoplasmas reproduction in chickens and stimulation of the immune response. Similarly, for groups 2 and 3, an age-related increase in the titer of anti-hemagglutinins to the H9N2 influenza virus indicated its replication in the body. In group 1 (vaccinated poultry), titers of antibodies to M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae, and H9N2 influenza virus also increased after infection depending on the age. However, it should be noted that on day 21 after vaccination, mycoplasmosis pathogens were also administered intramuscularly, which increased the immune response (a booster effect) and was accompanied by an increase in the titer of specific antibodies. At the same time, the absence of a clinically pronounced disease and histopathological changes in immunized birds indicated the vaccine effectiveness.

CONCLUSIONS

- Low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus (H9N2 subtype) with a zero intravenous pathogenicity index can be used as a co-infecting agent to assess the protective activity of mycoplasmosis vaccines during a laboratory challenge test.

- The co-infection of mycoplasmosis and low-pathogenicity avian influenza is manifested by a clinically pronounced disease and histopathological lesions.

- The clinically associated form of respiratory mycoplasmosis and infectious synovitis is reproduced in the laboratory after preliminary infection of poultry with the low-pathogenicity avian influenza H9N2 virus and is accompanied by mild respiratory disorders and joint failure. Histological examination of infected non-vaccinated birds revealed damaged tracheal ciliated epithelium with desquamation. A chicken vaccinated against mycoplasmosis and challenged with H9N2 influenza virus, M. gallisepticum and M. synoviae, showed no desquamation signs, however, local swelling of the submucosal layer was detected. Trachea morphological structure in control chickens was preserved, all layers were clearly visible.

- A significant increase in antibody titers after infection of chickens non-vaccinated against mycoplasmosis and low-pathogenicity avian influenza suggested pathogen reproduction in chickens.

References

1. Feberwee A., de Wit S., Dijkman R. Clinical expression, epidemiology, and monitoring of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae: anupdate.AvianPathology. 2022; 51 (1): 2–18. https://www.doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2021.1944605

2. Stipkovits L., Kempf I. Mycoplasmoses in poultry. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 1996; 15 (4): 1495–1525. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.15.4.986

3. Whithear K. G. Control of avian mycoplasmoses by vaccination. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 1996; 15 (4): 1527–1553. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.15.4.985

4. Animal mycoplasmoses. Ed. by Ya. R. Kovalenko. Мoscow: Kolos; 1976. 304 p. (in Russ.)

5. Bessarabov B. F., Vasilevich F. I., Melnikova I. I., Sushkova N. K., Chekmarev A. D. Guide on AvianDiseases. Moscow: KolosS; 2007. 200 p. (in Russ.)

6. Morrow C. J., Bradbury J. M., Gentle M. J., Thorp B. H. The development of lameness and bone deformity in the broiler following experimental infection with Mycoplasma gallisepticum or Mycoplasma synoviae. Avian Pathology. 1997; 26 (1): 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079459708419203

7. Irza V. N. Infectious synovitis birds – epizootiology and prevention. Ptitsevodstvo. 2009; (11): 39–40. https://elibrary.ru/ojzdet (in Russ.)

8. Yadav J. P., Tomar P., Singh Y., Khurana S. K. Insights on Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae infection in poultry: a systematic review. Animal Biotechnology. 2022; 33 (7): 1711–1720. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495398.2021.1908316

9. Prozorovskiĭ S. V., Pronin A. V., Sanin A. V. Immunologic mechanisms of the persistence of Mycoplasma. Vestnik Akademii Meditsinskikh Nauk SSSR. 1985; (10): 43–51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4082756 (in Russ.)

10. Chaidez-Ibarra M. A., Velazquez D. Z., Enriquez-Verdugo I., Castro del Campo N., Rodriguez-Gaxiola M. A., Montero-Pardo A., et al. Pooled molecular occurrence of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae in poultry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2022; 69 (5): 2499–2511. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14302

11. Catania S., Bilato D., Gobbo F., Granato A., Terregino C., Iob L., Nicholas R. A. J. Treatment of eggshell abnormalities and reduced egg production caused by Mycoplasma synoviae infection. AvianDiseases. 2010; 54 (2): 961–964. https://doi.org/10.1637/9121-110309-Case.1

12. Avian mycoplasmosis (Mycoplasma gallisepticum, M. synoviae). In: WOAH. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. 2021; Chapter 3.3.5. https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.03.05_AVIAN_MYCO.pdf

13. Avian influenza (including infection with high pathogenicity avian influenza viruses). In: WOAH. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. 2021; Chapter 3.3.4. https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.03.04_AI.pdf

14. Newcastle disease (infection withNewcastle disease virus). In: WOAH. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. 2021; Chapter 3.3.10. https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.03.10_NEWCASTLE_DIS.pdf

15. Sharavii A. O., Smirnova S. V., Polikarpov L. S., Ignatova I. A. Respiratornyi mikoplazmoz = Respiratory mycoplasmosis. Far Eastern Medical Journal. 2005; (4): 114–118. https://elibrary.ru/pkvydb (in Russ.)

16. Kleven S. H. Mycoplasmasin the etiology of multifactorial respiratory disease. Poultry Science. 1998; 77 (8): 1146–1149. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/77.8.1146

17. Roussan D. A., Khawaldeh G., Shaheen I. A. A survey of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synovaie with avian influenza H9 subtype in meat-type chicken in Jordan between 2011–2015. Poultry Science. 2015; 94 (7): 1499–1503. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pev119

18. Stipkovits L., Egyed L., Palfi V., Beres A., Pitlik E., Somogyi M., et al. Effect of low-pathogenicity influenza virus H3N8 infection on Mycoplasma gallisepticum infection of chickens. Avian Pathology. 2012; 41 (1): 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2011.635635

19. Volkov M. S., Varkentin A. V., Irza V. N. Spread of low pathogenic avian influenza А/Н9N2 in the world and Russian Federation. Challenges of disease eradication. Veterinary Science Today. 2019; (3): 51–56. https://doi.org/10.29326/2304-196X-2019-3-30-51-56

20. Kulappu Arachchige S. N., Wawegama N. K., Coppo M. J. C., Derseh H. B., Vaz P. K., Kanci Condello A., et al. Mucosal immune responses in the trachea after chronic infection with Mycoplasma gallisepticum in unvaccinated and vac cinated mature chickens. Cellular Microbiology. 2021; 23 (11):e13383. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.13383

About the Authors

D. A. KozlovRussian Federation

Dmitry A. Kozlov, Veterinarian, Laboratory for Avian Diseases Prevention

Yur’evets, Vladimir 600901

M. S. Volkov

Russian Federation

Mikhail S. Volkov, Dr. Sci. (Veterinary Medicine), Associate Professor, Head of Laboratory for Epizootology and Monitoring

Yur’evets, Vladimir 600901

O. A. Chupina

Russian Federation

Olga A. Chupina, Cand. Sci. (Biology), Deputy Head of the Centre for Preclinical Tests

Yur’evets, Vladimir 600901

N. V. Moroz

Russian Federation

Natalia V. Moroz, Cand. Sci. (Veterinary Medicine), Head of Laboratory for Avian Diseases Prevention

Yur’evets, Vladimir 600901

V. N. Irza

Russian Federation

Viktor N. Irza, Dr. Sci. (Veterinary Medicine), Associate Professor, Chief Researcher, Information and Analysis Centre

Yur’evets, Vladimir 600901

V. V. Pronin

Russian Federation

Valery V. Pronin, Dr. Sci. (Biology), Professor, Deputy Director

bldg. 1, Akademika Bakulova str., Volginsky 601125, Petushinsky District, Vladimir Oblast

Review

For citations:

Kozlov D.A., Volkov M.S., Chupina O.A., Moroz N.V., Irza V.N., Pronin V.V. Creating a laboratory model of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae associated infection. Veterinary Science Today. 2025;14(1):55-61. https://doi.org/10.29326/2304-196X-2025-14-1-55-61

JATS XML